Tom of Finland’s Explicit Art Radically Changed How We View Gay Sexuality

When Touko Laaksonen, better known as Tom of Finland, began publishing and exhibiting his drawings of muscled and mustachioed gay men in the 1950s, his artwork was still illegal in many places. Anti-gay censorship laws meant he and his collectors could be imprisoned for owning same-sex erotica. But over the course of his artistic career, which spanned more than 60 years and produced over 3,500 works, Tom of Finland inspired a legion of queer artists and changed the way the world views gay masculinity and sexuality.

Born in rural Finland in 1920, Laaksonen was a talented artist from an early age, and his schoolteacher parents encouraged his academic and creative pursuits. But according to his biographers, he also spent his childhood spying on the muscular boys working on neighboring farms. In 1939, he went to art school in Helsinki, where more cosmopolitan expressions of masculinity caught his imagination. Over time, depictions of gay men dressed as day laborers, seafarers, and motorcyclists became a motif that appeared in much of his work.

When Stalin invaded Finland during World War II, Laaksonen was drafted into the military, and during blackouts he started having clandestine sex with uniformed men on both sides of the conflict. Peace brought an end to these encounters, and Laaksonen went back to studying art, largely confining his desires to his sketchpad except for chance cruising encounters.

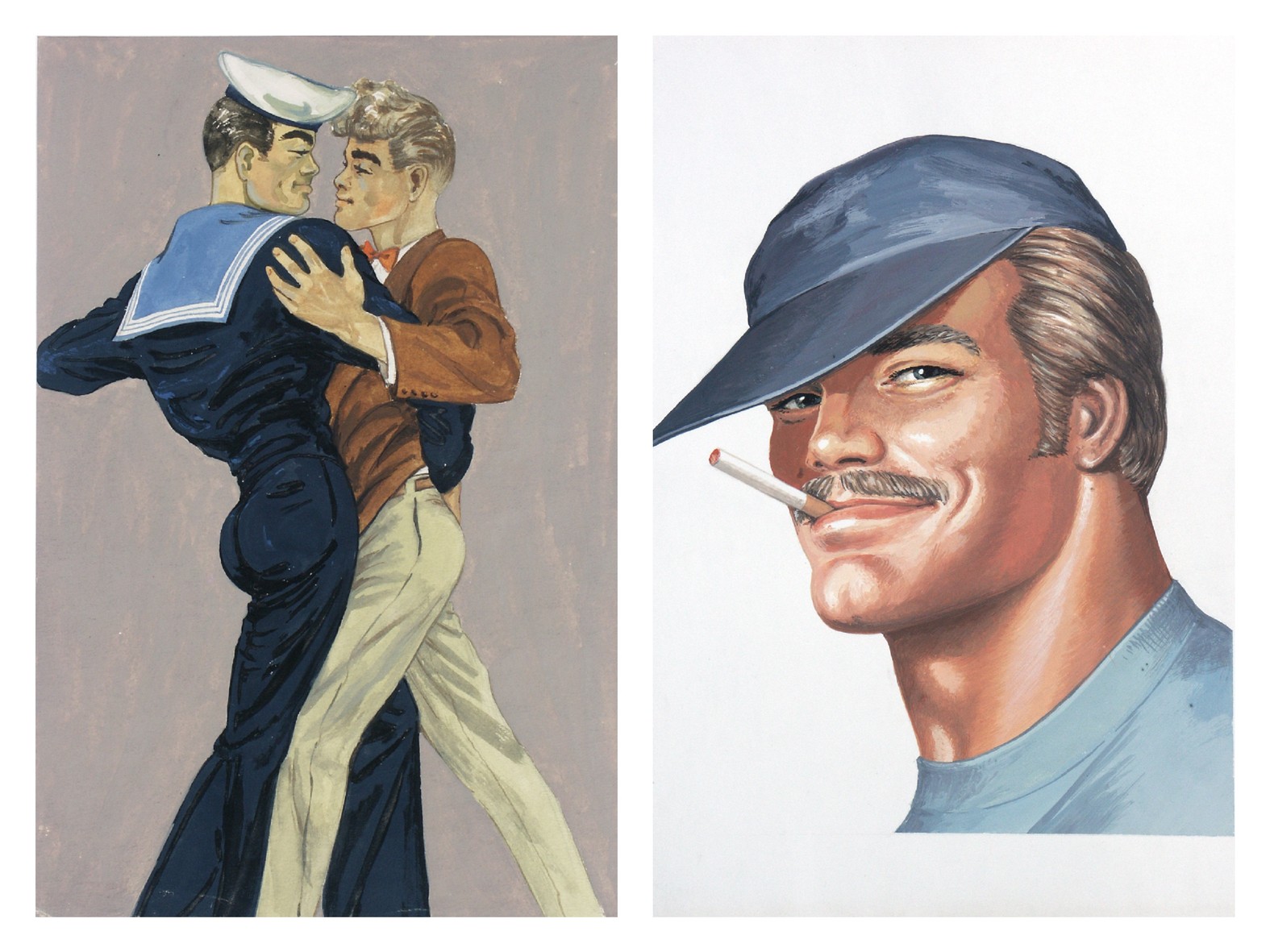

Left: Tom Of Finland, Untitled, 1947. Right: Tom of Finland, Untitled (From Kake vol. 20 - Pleasure Park), 1977. Courtesy Tom of Finland Foundation and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, California

In 1956, he submitted an illustration of a muscular lumberjack with a bulging crotch to Physique Pictorial, an American magazine that passed itself off as a sports rag to skirt censorship. It was popular with gay men who'd lust after the nude or semi-nude bodies of the muscled models. To protect his identity, Laaksonen simply signed the work “Tom.” When the drawing landed on the cover in the spring of 1957, the editors changed his name to “Tom of Finland," and a cultural icon was born.

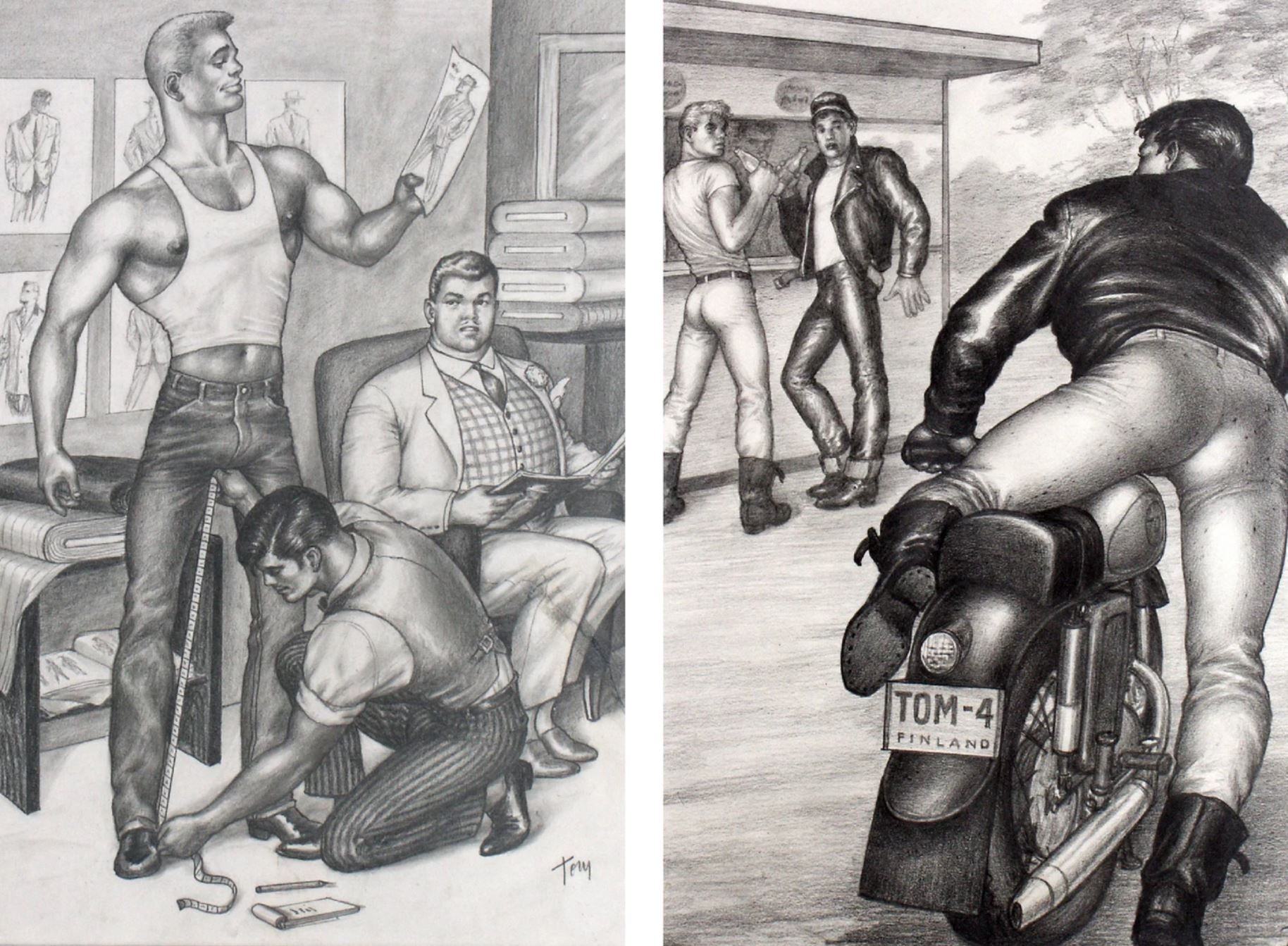

In the 50s and 60s, beefcake art focused on depictions of beautiful male bodies, sometimes in proximity to one another, but never interacting in a sexual sense. “What Tom recognized was that a lot of the depictions [in queer culture] were beefcake,” S.R. Sharp, the Vice President of the Tom of Finland Foundation, told VICE.

“We were just voyeurs looking at models that we didn’t know anything about. Were they just models? Were they gay? Were they straight? Were they being paid? We didn’t know. We were just voyeurs looking at beefcake. Tom said, ‘I can fix that,’ and so he made a deliberate effort to bring beefcake into [fine art,]” Sharp added.

Left: Tom of Finland, Tom’s Finnish Tango, 1947. Right: Tom of Finland, Untitled (Portrait of Pekka), 1975. Courtesy Tom of Finland Foundation and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

Though many of Tom’s early works didn’t explicitly depict sex, their characters still interact, gazing at one another with lust that, to that point, had not been a hallmark of the genre. “When you saw Tom’s subjects, even when they were fully clothed in the mid 50s, you knew they had a ‘gaze’ about them,” Sharp said. “They had a way that they looked at each other—a way that they cruised each other—that let you know they were, indeed, queer.”

As Laaksonen’s star rose, he continued publishing works that subtly pushed the envelope, while taking on more explicit private commissions. But it wasn’t until the mid-70s that Tom of Finland became renowned for his raunchy, photorealistic illustrations of muscular gay men enjoying sex. It was a paradigm shift that helped fundamentally change the way gay sexuality was viewed by the mainstream.

Very few artists were working in the same way as Tom of Finland, injecting same-sex lust and tension into their art. But it’s worth noting that Roland Caillaux, a lesser known actor and artist, was creating similar work in Paris a decade before Tom of Finland found success. He was treading similar ground, depicting men in naval uniforms and states of undress. They were leaner than Laaksonen’s, but had the same gaze about them, fondling one another and engaging in sex. But with a groundswell of American support, Tom of Finland became more widely shared, sparking kinship and recognition in the men who viewed his art.

“It made it so we could see a relationship, and even if you were in a small town and you were 15 years old and didn’t know how to identify yourself, you knew there was a similarity between yourself and what you were seeing on paper,” Sharp explained. That recognition translated into visibility for the queer community and helped lay the blueprint, in part, for leather and fetish communities that were beginning to form.

Left: Tom Of Finland, Untitled, 1959. Right: Tom of Finland, Untitled (from "Motorcycle Thief" series), 1964. Courtesy of Tom of Finland Foundation and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

In the 1970s, men were using the art to re-enact scenes that Laaksonen had experienced during the war, finding each other in seedy bars, alleys, and cruising spots in parks around the world. They dressed themselves like Tom of Finland characters, starting “motorcycle clubs with no motorcycles” that were the beginnings of the leather community.

In addition to this generation of gay men, his work influenced a generation of artists. As Laaksonen began spending more time in America, he grew close to artists like Etienne and Robert Mapplethorpe, inviting them to his home for salons and viewings, since opportunities to show their work at public institutions were scarce. “I think Tom gave them permission to use erotica as a part of their practice,” Sharp said. “He made them think that they could examine what they were doing and know that they could incorporate sexuality into their work.”

Their art changed the visuals of queer culture, not only by showing work in magazines and later galleries, but also by doing the graphics for iconic fetish clubs like Mineshaft and The Lure, gay bathhouses, and a variety of other queer establishments. That influence continues to resonate with artists today, as noted in books like My Gay Eye, which includes current working artists like Gio Black Peter, who recently helped conceptualize the artistic direction for the legendary New York queer fetish event The Black Party.

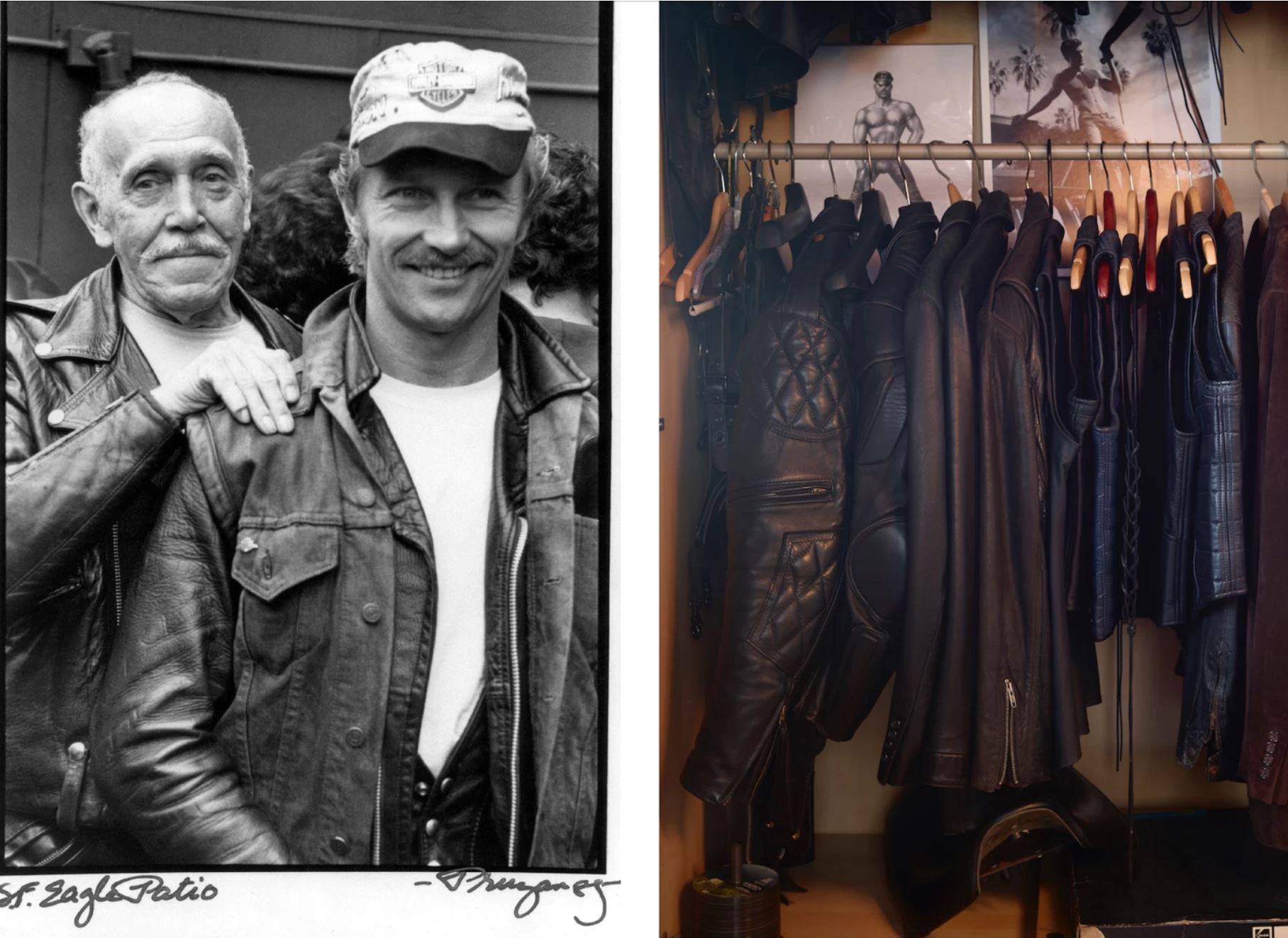

Left: Laaksonen and his protégé Durk Dehner at a fundraiser for the Foundation at the Eagle in San Francisco, 1985. Photo: Robert Pruzan. Right: Leather jackets hanging inside TOM House, Los Angeles. Photo: Martyn Thompson. As featured in the book TOM HOUSE, published by Rizzoli.

Tom of Finland’s enduring legacy is woven into a new exhibition, TOM House: The Work and Life of Tom of Finland , within Mike Kelley’s Mobile Homestead at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). Featuring a newly-built fireplace and oriental rugs, the single-story ranch house has been redecorated to look like the TOM House in Echo Park, Los Angeles, where Laaksonen spent half of each year in the final decade of his life. It was the space where he socialized and interacted with many of the queer artists he influenced.

Interior of TOM House, Los Angeles. Photo: Martyn Thompson. As featured in the book TOM HOUSE, published by Rizzoli.

At MOCAD, Tom of Finland pieces hang alongside work by Mapplethorpe, Raymond Pettibon, John Waters, and other contemporaries influenced by his art. Early drawings and reference materials—Laaksonen’s work was often an amalgamation of his imagination and men in his life—are shown alongside more polished drawings. One hallway features his Pleasure Park series, depicting a figure named Kake on a cruising trip-turned-orgy in the woods. In the garage, four vitrines feature ephemera, like fliers from 1999 for the punk band Limp Wrist featuring appropriated Tom of Finland illustrations.

“Tom of Finland’s work has the power to change people’s lives and make people feel like who they are is important,” said Elysia Borowy-Reeder, the Executive Director of (MOCAD). “That has a big political message, particularly today.”

His work was undoubtedly formative—not only for queer artists and the gay community at large, but for societal misfits of all walks of life. Most notably, it offered a level of visibility for queer men in ways that hadn’t popularly been depicted in art before. But more than that, the pieces specifically affirmed queer sex in its many expressions, in ways that flew in the face of respectability politics and changed the way society viewed gay sexuality forever.